A Fiery Finale: Cafe Brulot in New Orleans’ old-line restaurants

By Kim Ranjbar

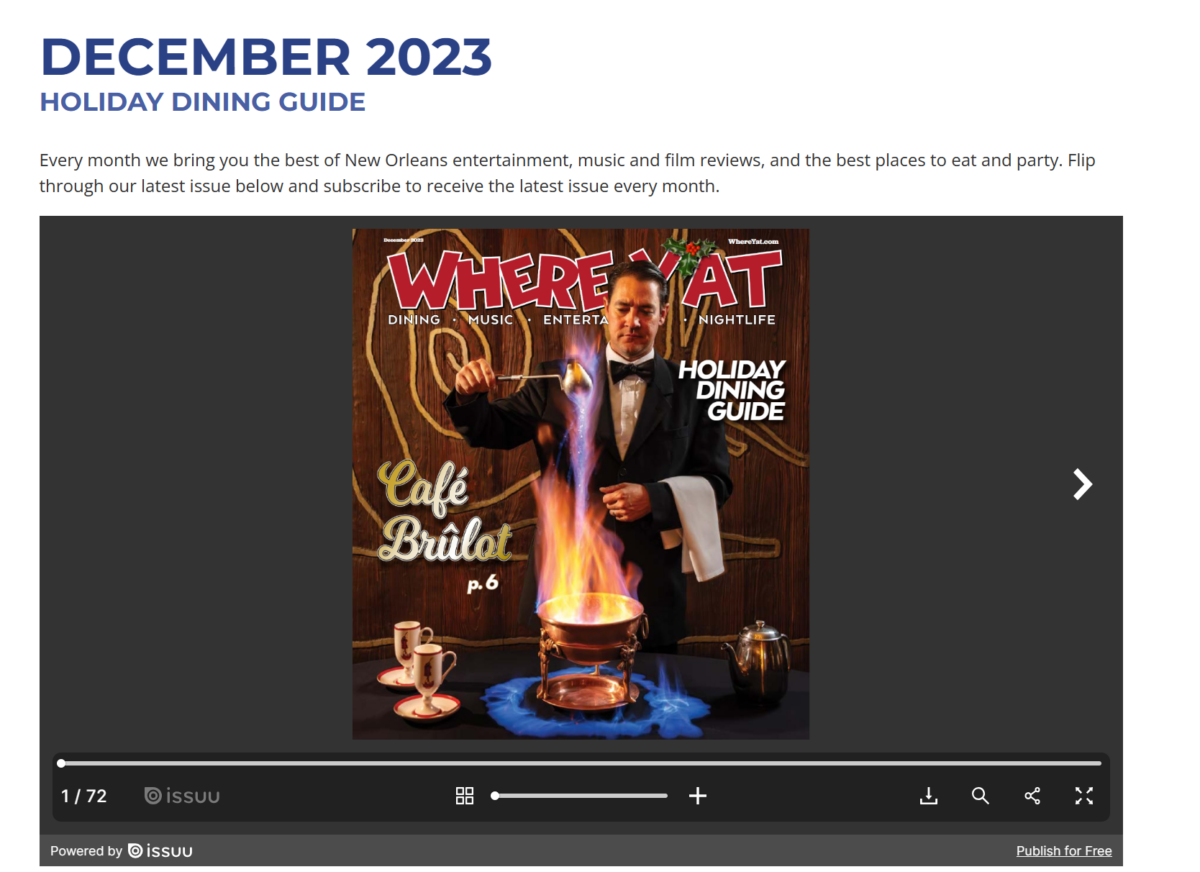

A hallmark of a bygone era, table side preparation and presentation of Café Brûlot perseveres in New Orleans’ old-line restaurants.

It’s a blustery winter evening, but on the inside of Antoine’s French doors, you’re rosy-cheeked and cozy. Leaning back after indulging in a veritable feast of crisp souffle potatoes dipped in béarnaise and buttery Gulf fish amandine heaped with sauteed lump crab, you’re taking a little breather while considering dessert. After many deep-bellied sighs and wide smiles of content, you decide to pair your apple bread pudding, served in a sweet pool of rum raisin sauce, with a warm coffee cocktail—not just any coffee cocktail—a café brûlot diabolique.

Your gracious server, dressed in a black suit and bow tie, rolls out the guéridon and proceeds

to awe and amaze. He performs dazzling feats of table-side pyrotechnics, lighting a silver bowl of the brandy-based concoction and confidently ladling the flaming liquid over a half-peeled orange held well above the bowl, almost as if he’s inviting disaster to strike. As the curl of rind studded with cloves is doused in brandied flames, a nostalgic, Christmassy aroma fills the dining room, attracting the attention of diners not already entranced by the fiery display. With a final flourish, the skilled server pours rich, hot chicory coffee into the bowl. While at first the flames rise higher, they’re finally extinguished, transformed into puffs of aromatic steam.

Various lore surrounds the origin of café brûlot, but it’s generally agreed upon the first was concocted by Jules Alciatore, son of Antoine Alciatore who founded Antoine’s Restaurant in 1840. Schooled at his mother’s side in the restaurant and later in some of the finest kitchens in France, Jules’ culinary skills and creativity propelled the family business forward with great success. Antoine’s Restaurant’s world-famous dish oysters Rockefeller can be credited to Jules. In 1899, there was shortage in snail shipments from overseas, and Jules, taking advantage of local abundance, created an escargot dish made from Gulf oysters and the rest is history. It’s not a giant leap to believe his culinary acumen also created the devilishly delightful café brûlot diabolique.

Another theory includes the almost inevitable involvement of famed local pirate Jean Lafitte, an oft-sung hero who helped save the city in 1812 during the Battle of New Orleans. According to New York mix master Dale DeGroff, café brûlot’s creation was inspired by Lafitte’s “drink-making theatrics,” setting his liquor ablaze in a crowd to distract onlookers while his cohorts lightened their pockets. Yet another story postulates that the café brûlot was the product of 1920s prohibition. The rich chicory coffee and earthy spices served in demitasse cups was all said to hide the presence of alcohol, but Sue Strachan, author of The Café Brûlot, is not convinced. “You need alcohol to flame the drink,” says Strachan. “That story never really made sense to me.”

Published by the Louisiana State University Press in 2021, The Café Brûlot explores several “ifs” and “may have beens” surrounding the creation of New Orleans’ most incendiary beverage. Though most of her discoveries still center on Jules Alciatore’s diabolical drink at Antoine’s, there’s also a distinct influence coming from the Armagnac region of France.

La Flamme de l’Armagnac is an annual three-month festival in Gascony, France that celebrates the creation of yet another successful batch of brandy. As part of the festivities, brûlot is made by placing the full-alcohol, newly-distilled (a.k.a. white) Armagnac and rock sugar in a large copper bowl and lighting the mixture on fire. For about 30 minutes, they stir the fiery bowl of brandy with a long, copper ladle until the sugar melts and some of the alcohol burns off. Then dried fruits, vanilla, citrus, cloves, and other ingredients (every recipe is different) are added before serving. Sometimes the brûlot is served with coffee, but sometimes it’s not.

Today you can still enjoy café brûlot at Antoine’s, as well as several other New Orleans’ grande dame restaurants such as Arnaud’s, Galatoire’s, and Commander’s Palace, all of which boast “haute Creole cuisine.” At its most basic, the recipe for café brûlot is brandy, orange liqueur, citrus oil, sugar, cloves, cinnamon, and coffee, but as is true for any recipe, there are always variations on the theme.

While writing The Café Brûlot, Strachan was treated to multiple tastings with varying ingredients at Antoine’s Restaurant. She experienced how even little changes could alter the overall flavor of the finished cocktail. “Charles Carter, who’s one of the legacy waiters [at Antoine’s], made all of these different iterations,” explains Strachan. “I tasted it with French roast coffee, and then I tasted it with coffee and chicory. Instead of orange liqueur, I tasted it with Kirschwasser (cherry liqueur).”

For those seeking to make it at home, café brûlot is not for the faint of heart. In her book, Strachan rightly warns intrepid, amateur mixologists to always be prepared with a fire extinguisher close at hand. That being said, Strachan discovered that making café brûlot is sort of an annual tradition for some New Orleans families. “Edith Stern, the Longue Vue Gardens Edith Stern, used to make her own,” says Strachan. “It’s sort of its own tradition.”

While researching and writing The Café Brûlot, Strachan could find little or no evidence of mishap around the incendiary coffee drink, but after it was published, stories began to trickle in. One woman revealed an incident when her nephew was making the cocktail too close to their grass cloth wallpaper. Though the flame was extinguished, the danger was real. It’s probably safer to reserve a table at Antoine’s.

See the full story in the December 2023 issue of Where Y’at Magazine: https://issuu.com/whereyatnola/docs/14_dec23-hdg-issuu